There is lots of talk about what DevOps is and means, even a Wikipedia page, to which I may soon give some much needed love. However, a friend recently asked if I knew anyone worth hiring for a “devops” role, and I found myself asking clarifying questions about the sort of person he had in mind. Seemed worth writing down.

The friend was looking for engineers. So what does it mean for an engineer to be devops-y?

TL;DR

- Understand the Whole Company as a System

- Respect Other Functions Within The Organization Profoundly

- Have a Strong Sense of Personal Accountability

Build your software like you give a shit about the people whose jobs and lives are affected by it.

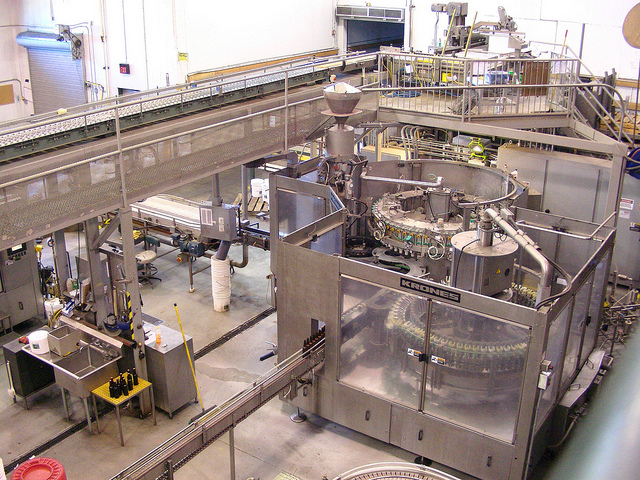

1. Understand the Whole Company as a System

Photo by verifex

Your company has inputs (money, labor, etc) and outputs (product, money, etc). I’ve grown to loathe the phrase “above my pay grade” because it tends to betray a complete lack of interest in the big picture. Hanging around my new colleague Jim, aka Mr Manager, I’ve recently started to identify things as “tactical” vs “strategic.” Strategic is the big picture - where is the company going; what are the company’s goals; what will make or break our success. Tactical is the every day - what features are left on the current project and which one should I work on next; how much time should I spend on this bug, what with the massive deadline looming; hell, should I even be looking at bugs? If you don’t have a good grip on how you and your project fit into the bigger picture of the company, you are always tactical. Tactical can quickly become boring, repetitive, and un-rewarding. It’s also a nice way to never grow as an individual. In the DevOps picture, it means you probably don’t make judgment calls well with regards to what is and isn’t important, distributing your time poorly. Your colleagues probably notice; they probably don’t like it.

This is a great segue to:

2. Respect Other Functions Within The Organization Profoundly

For our immediate purposes, we can focus on just the ops team, but it applies well beyond. Understanding and respecting the priorities and needs of non-technical teams and taking them seriously helps greatly reduce the number of surprises on both sides. Also, if you’re really living number 1 above, you probably won’t be surprised that your goals are very closely related.

But back to your relationship with the ops team (or, if you’re living in devops dream land, your colleagues, since you’re all part of the combined devops utopia, right?) What makes them tick? What wakes or keeps them up at night? What makes their job harder? Easier? I like to make it personal: how have I made their lives better or worse?

Let’s look inwards for a moment: what if someone is asking these questions about me? Well, I’m a software engineer. I grind code for a living. I get some requirements (new product spec, a bug, something I think up in my free time and don’t tell anyone about, etc), figure out how to meet those requirements, write some code, and push it to production.

What are the things that make me happy while performing these functions? Well, there’s a whole bunch of them, but they can all be summed up very easily: lack of friction. A relatively low number of things I have to do beyond my core activities in order to get to the end; a limited number of context switches. A clean, consistent, reproducible dev environment. A responsive, intelligible build system. A mostly-automated way of moving my code through various environments.

What has ops done for me?

Well, shit, I’m actually mad spoiled. Flickr was a PHP site with a well oiled deploy machine that we’ve all heard about - since you didn’t need to restart anything to get your code out (an under-appreciated side effect of the way PHP is traditionally served), we’d literally just push a button and the new code got rsynced to the boxes while also keeping a nice, visible record of the what, when, and why (a form of this now available to the masses in the form of Etsy’s Deployinator). SimpleGeo and Urban Airship use(d) Puppet and Chef respectively to great success, and there was an ever-improving set of tools available to make it easier to start working on a project and to test it as I went along. When I was done, it got reviewed, merged, built and sent off to a package repo, then deployed to production using automation. I spent most of my time actually debugging or writing code, not sheparding it around environments or struggling to get it to run in the first place. It’s also easy to forget the little things that helped keep computers out of my way - federated logins etc.

These are just the more salient examples - specific things ops has done to make my life easier; it is by no means an exhaustive list of what I see as the core strength of my prior ops teams.

What have I done for ops?

Photo by Business

Insider

Let’s look at what my teams at each of these orgs did that I think was helpful to and appreciated by the ops teams. This is in no particular order, and I’m going to forego the names of the organizations because there’s a ton of overlap.

- Painstakingly instrumented our services so that their state could be more easily examined in the wild

- Pumped as much data as we could into the monitoring tools kindly provided us

- Thoughtfully considered what metrics and properties were helpful in determining the health of each particular system being worked on. Business people might call this a KPI; Mathias Meyer called it a “Soul Metric” in his monitorama talk.

- Carefully set up alerts that interpreted the above to try to minimize noise and non-actionable alerts.

- Learned at least enough about the configuration management tools to be able to submit pull requests for desired changes in production without personal involvement and hand holding from someone on the ops team.

- Considered and tested how the software being written behaved itself before an emergency - how is failover handled? how are configuration changes handled?

- Automated or helped automate parts of the process that were difficult to remember or tedious.

- Worked on tools in our spare time that made any of the above easier.

Broadly, we tried to be sensitive to how the operators interacted with the thing in production and how reasonable the experience was - during changes, during outages and failures, etc. We focused on operability.

Why did we do all this?

3. Have a Strong Sense of Personal Accountability

Because it felt like the right thing to do. When people got woken up at three in the morning because something I had deployed broke in a confusing, difficult-to-debug way, it felt bad. I wanted it to be less confusing the next time. If we’re being honest with ourselves, it probably helped with the motivation that I woke up too and was just as frustrated and annoyed.

Go back to #2 and think “Do people in the other organizations have the right tools to perform their jobs?” The better the tools, the less friction there is, the more quickly people can perform their reactive tasks (ops responding to pages; marketing compiling a traffic report that the CEO suddenly needs for a board meeting; support dealing with a massive DDoS or spam influx) The less time people spend reacting, the better - reacting is by definition tactical, and spending all your time in tactical mode, as we’ve covered, is not great. The list in section 2 was focused on ops, but a lot of the same stuff, especially the tools bit, applies to other teams as well.

It’ll never be perfect, but often the smallest change makes the biggest difference. Re-arranging a dashboard ever-so-slightly could be the difference between someone getting RSI while trying to track down spammers until late at night and them going home in time for dinner. A good DevOps engineer in my mind is one that feels personally responsible and accountable for the parts of his or her job that have an effect on colleagues’ happiness and success. Remember, everyone likes going home for dinner.

Conclusion

Coming back to what this all means for a software engineer: it’s all about the big picture. In an organization whose primary output is software, everybody depends on how well that software is equipped to help them succeed in their particular job. Understanding your effect on these needs and striving to meet them - that’s what DevOps means to me.

Further Reading

- DevOps: These Soft Parts A post by John Allspaw about the soft skills involved in making DevOps-style cooperation work

- Developing Operability (slides) A talk to Richard Crowley with specific advice for smoothing the journey of code to production for both devs and operators; more on the meaning of “DevOps” (warning: a wall of text)

- DevOps - The Title Match A post by John Vincent on a common misconception about the organizational meaning of DevOps