This is the story of an outage that occurred on September 25th 2014 and has previously been discussed in the context of blameless post mortems on the PagerDuty blog.

If you attended Surge 2014, you may have noticed something strange: a man was sitting on one of the cube-shaped stools in the Fastly expo area hunched over his laptop almost the entire day, and well into the evening hours. Even if you didn’t notice, and even if you weren’t even AT the conference, you may be curious about this man. The security guard certainly was, as he made his rounds after dark, long after everyone had left the expo area..

That man was yours truly; I was fixin’ stuff. This is the story of what happened.

The Outage

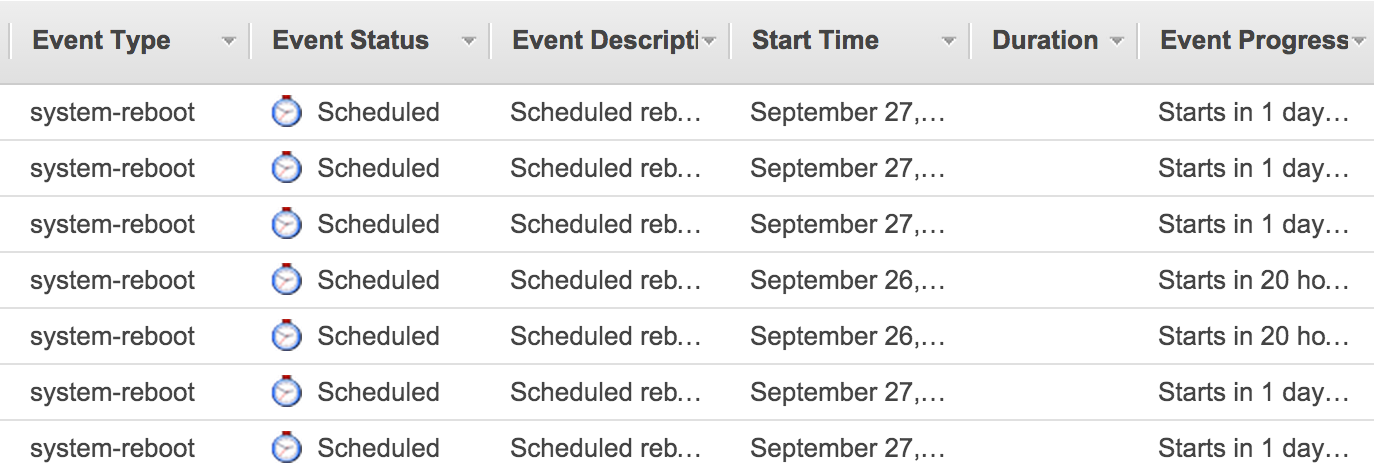

On September 24th Opsmatic was one of the many AWS customers to receive one of these emails:

One or more of your Amazon EC2 instances are scheduled to be rebooted for required host maintenance. The maintenance will occur sometime during the window provided for each instance. Each instance will experience a clean reboot and will be unavailable while the updates are applied to the underlying host. This generally takes no more than a few minutes to complete.

The EC2 Event Console confirmed that quite a few instances in our infrastructure would be affected:

All the servers would be rebooted early Friday or Saturday morning SF time.. while I was at the conference. There was not much certainty in the exact timing or order of the reboots (the windows were 4 hours long), but we did eventually discover some good news:

- Any instances using EBS for their root volume could be put through a stop/start cycle in advance of the window to avoid the reboot. When you “stop” an instance, you’re essentially destroying it, but the EBS volume survives. When you “start” it back up, you get no guarantees about which “host” will receive the instance that will then boot that volume. This is where “ephemeral” drives get their names - they are attached to the “host” and do not survive a stop/start.

- Any instances provisioned after the notifications went out would not need to be rebooted. As we later learned, the reboots were necessary for Amazon to roll out a patch to Xen which fixed XSA 108. Many hypervisor “hosts” were already running patched code, so Amazon would simply put new instances on already-patched hosts.

Since every single piece of Opsmatic’s infrastructure is redundant at least at the instance level, we quickly concluded that this was actually not that big of a deal:

- All of our nodes used EBS root volumes, so they could be stop/started

- Most of our nodes do not use ephemeral storage for anything important

- The affected nodes that DID use ephemeral storage were Cassandra nodes. Since we use a replication factor of 3, we can afford to have at least one of those rebooted at any time.

We briefly debated pre-emptively re-provisioning the Cassandra nodes anyway, but decided that it was better to just let the reboot happen. Copying data is time consuming, and the reboots were hours away. We would just get up just before the maintenance window started and gracefully stop Cassandra on the node about to be rebooted out of an over-abundance of caution.

To minimize the amount of odd-hours activity, we decided to stop/start all the stateless nodes that were scheduled to be rebooted on our own terms, during business hours. Since I was already at a conference, I’d take care of it in order to minimize disruption to the rest of the team back home, cranking away.

At around 13:50 PDT I started the process. I stop/started one of our NAT nodes without incident. Then things get a little murky.

For some reason, I decided to actually replace one of the nodes, but I don’t remember why. I did not make any record of my reasoning. It is entirely possible that I got distracted between the last node and the next one and went to reprovision it instead of just doing a stop/start cycle. It’s also possible there was some other issue with the node, and I simply failed to document it.

At about 14:15 PDT, I terminated one of our “stack” nodes (they run all the services that power the Opsmatic app) and then went to replace it.

We had provisioned our AWS infrastructure using Chef Metal so replacing the node should have been as simple as terminating it and then “converging” the infrastructure - a single, global command that does not take any parameters other than the declaration of what your infrastructure should look like (number of nodes in each cluster, etc). Chef, in theory, would detect that the “stack” cluster was missing a node and provision a new one to replace it.

So that is what I did. Replacing a node in our infrastructure is a routine operation that we had practiced several times without incident.

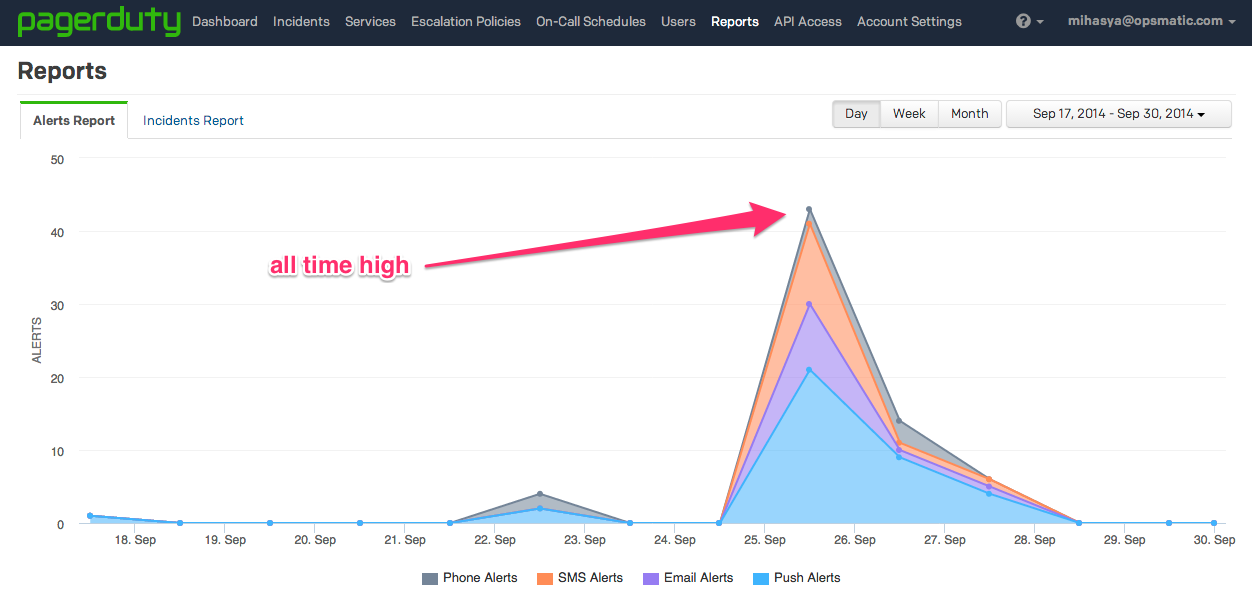

At 14:20 PDT Opsmatic went down in flames. The Chef run restarted every single instance in our infrastructure.

Talk about a “Game Day”…

As soon as the instances came back up, we scrambled to make sure that all the services were back to normal. We were down for a total of about 30 minutes, in part because there were certain parts of the recovery process that were not as smoothly automated as we had thought; these defects became very apparent during the previously un-tested “restart the entire infrastructure” scenario.

The Causes

Once service was restored, we started trying to figure out what the hell had happened. Meanwhile, the delightful Surge lightning talks were drawing uproarious laughter in the main ballroom behind me.

As I scrolled frantically through the log from my fateful Chef run, I saw a bunch of lines like this:

[2014-09-25T21:18:39+00:00] WARN: Machine ******.opsmatic.com (i-*******

on fog:AWS:************:*********) was started but SSH did not come up.

Rebooting machine in an attempt to unstick it ...

One per server. We quickly confirmed in the #chef IRC channel that this was a

bug - because Chef could not establish an SSH connection to these nodes,

it decided to reboot them. That, apparently, should not have happened.

[2014-09-25T18:30:13-0400]

<johnewart> Ah, well -- you managed to uncover a bug by doing that

<johnewart> we should only reboot it if it's within the first 10 minute window

<johnewart> like, you create, and then try to run again 5 minutes later and it can't connect

After a bit more digging, we sorted out that chef-metal had been relying on

the ubuntu user being present on all our machines along with a specific

private key. Something had caused the home directory for the ubuntu user to be

deleted.

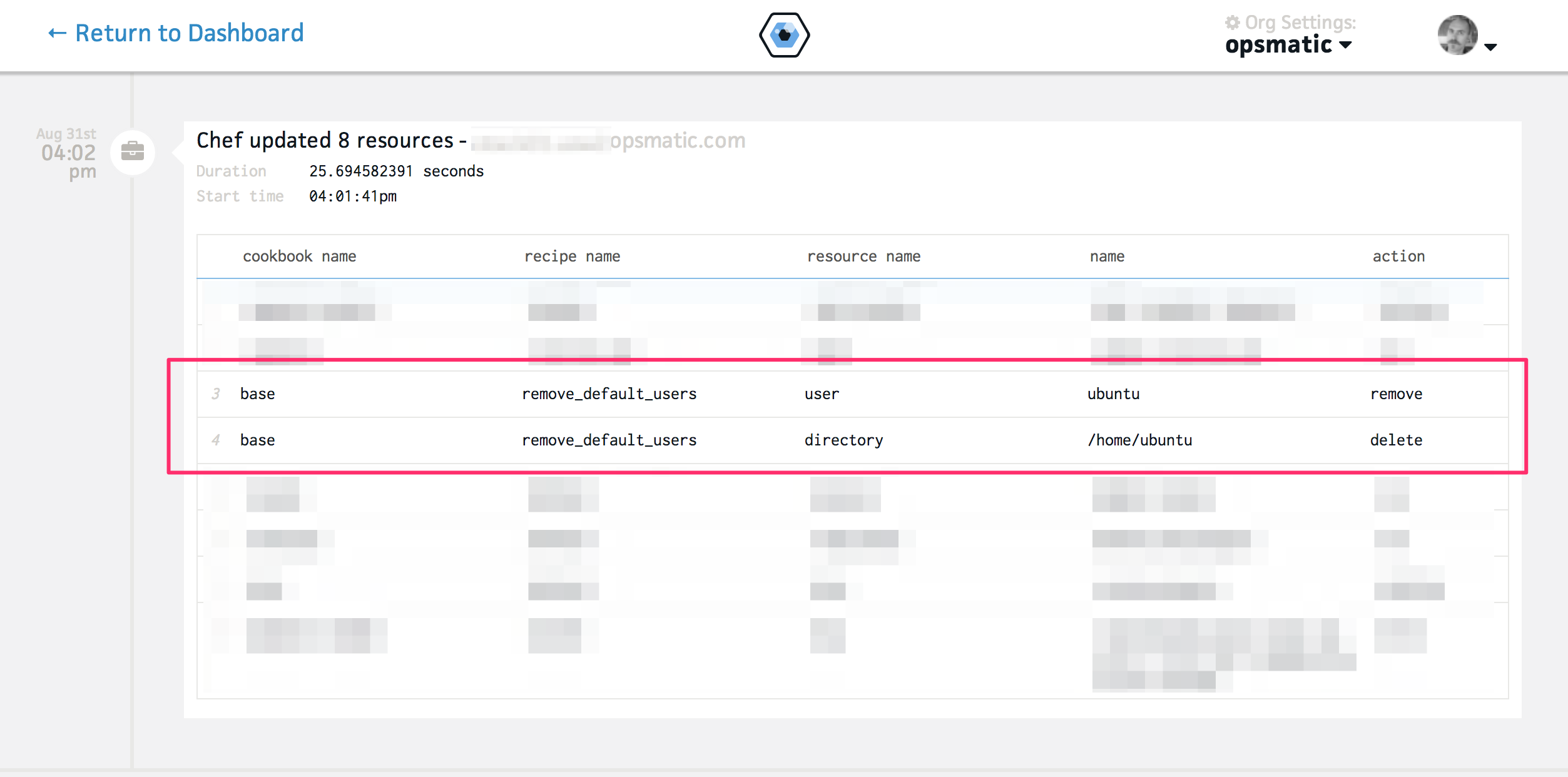

At this point I remembered something: a LONG time ago, before Opsmatic even had

a name, I had done some experiments with AWS. As part of that, I had a

bootstrapping scheme which relied on the same ubuntu user (standard practice

when provisioning Ubuntu AMIs), but also included a recipe called

remove_default_users which nuked the ubuntu user once bootstrap was

complete.

This bootstrap process was never used for anything serious - the initial

iteration of Opsmatic’s infrastructure was one big server at an MSP; from there,

we moved straight to the Chef-driven AWS setup. However, that small bit

of cruft persevered in our chef-repo.

My hunch was correct. Although remove_default_users was never part of any

roles or run lists in the new infrastructture, we were able to confirm that it

was applied on all the nodes on August 31st (just a couple of days after the

last time we had practiced replacing a node) by performing a search in Opsmatic

itself:

However, by the time of the outage it was once again absent from all run lists. So how did it get there on August 31st and how was it ultimately removed? That would take another couple of weeks to figure out.

The remove_default_users recipe was clearly dead weight; we had gotten a

little sloppy and let a bit of invisible technical debt accumulate. In order to

prevent the same thing happening again, we immediately deleted the recipe. This

has another nice side-effect: the next time this recipe appeared in a run list,

Chef would fail. We have good visibility into those failures in Opsmatic, so we

would be able to react and debug “in the moment.”

That exact thing happened on October 14th: as I was doing some

refactoring in our cookbooks and roles, I found chef failing because it could

not find remove_default_users. I knew I was about to find something important

- something slippery, elusive, confusing, and damaging. Indeed.

The recipe was originally part of a cookbook called base - a collection of

resources that needed to be applied to all nodes. As we moved to a

“more-than-one-node” setup, we started using Chef roles to define run lists. The

base cookbook was pulled apart and reconstituted as a role to be included in

other roles. There was a step in the refactor where “parity” was achieved - the

role was made to replicate the previous behavior exactly. At that point, the

role was copied into another file called base-original.json to be used as a

reference as pieces of it were pulled into other cookbooks etc. Many edits were

then made to the role in the base.json file.

The base-original.json file stuck around in the roles directory.

But here’s the thing about a role file: unlike cookbooks, the name of the role

doesn’t just come from the filename; it comes from the name field defined

inside.

$ head roles/base.json

{

"name": "base",

"description": "base role configures all the defaults every host should have",

"json_class": "Chef::Role",

...

$ head roles/base-original.json

{

"name": "base",

"description": "base role configures all the defaults every host should have",

"json_class": "Chef::Role",

...

The majority of time spent working on Chef is spent working on cookbooks, so it’s easy to forget the subtle differences in behavior with roles.

So what had happened was this: while modifying something else about the base

role, I had assumed that base and base-original were different roles that

were both in use. I had modified both files and uploaded them both to the Chef

server, first base, then base-original. In reality, they both updated the

same role, and the base-original content won out because it was uploaded

second. Chef ran at least once with this configuration, deleting the ubuntu

user. Some time later, someone who DID know that base-original was not to be

uploaded made yet more changes and only uploaded base, wiping

remove_default_users out once more. By the time the epic reboot happened, it

was gone from the run list again, leaving us to scratch our heads.

Because the ubuntu user was created by the provisioning process and not

explicitly managed by Chef, it was not re-created.

Whoever ran chef-metal next was going to cause a global reboot. It just so

happened that I did it from a conference and ended up spending my evening

plugged into an expo booth’s outlet.

Remediations and Learnings

Computers are Hard

Managing even a small infrastructure requires discipline, precision, and thoroughness. The smallest bit of cruft can combine with other bits of cruft to form a cruft snowball (cruftball?) of considerable heft over a relatively short time period.

Cookbooks vs Roles

This sort of failure is exactly the cause of the trend towards “role cookbooks”

replacing the role primitive. Having a recipe that is simply a collection of

other recipes is functionally identical to a role, but has a few advantages -

namely versioning (enough said) and consistent behavior with resource cookbooks.

Having a recipe named base-original.rb would have had no effect on a recipe

named base.rb.

chef-metal

While the theory behind chef-metal sounds good, we have started switching away

from it. Bugs and maturity are the immediate problems, but it would be foolish

to act like those don’t exist in all software, including whatever other scheme

we end up using. This single bug is not why we’re migrating away.

The theory behind chef-metal itself sounds good, and it’s the

“right” sort of automation, e.g. it’s not just scripting steps normally

performed by a human

However, it was very alarming how easily a very localized, routine change which

had been successfully executed fairly recently turned into a global disaster.

This is a big red flag for any system. It is an indicator of unnecessary

coupling. Every time we wanted to add any node to our infrastructure, however minor

and auxiliary, we’d have to perform an operation that touches everything.

Having witnessed the potential for disaster, this would elicit a healthy dose of

The Fear each time. In the long run, if we’re afraid to perform simple tasks

with the the provisioning system, we’re not going to provision and replace nodes

as frequently. Whenever you stop doing something regularly, you become bad at

it. Routine operations should have routine consequences.

There are also more tactical concerns: “can’t SSH to this server, better reboot

it” sounds EXACTLY like automating a manual ops process, and a bad one at that.

Then there’s the security angle: even with the bug fixed, chef-metal still

requires SSH access to the servers it manages with elevated credentials. In

other words, you have to keep the provisioning user (ubuntu in our case)

around on your instances forever. We strongly dislike that - it adds another

little bit to the surface area. Sure, you need to be on a private network in

order to get to SSH in the first place, but it’s another hidden back door that’s

easy to neglect. We’d rather not have it.

We haven’t had much time to think about it, but this approach may work much better when applied at the container level, one step removed from the actual infrastructure. We may investigate it in the future. For now, our infrastructure is small, homogenous and simple enough that we will simply be switching to a more “transactional” provisioning process.

Documenting and Finishing Big Migrations Quickly

A huge part of this was just technical debt - recipes, cookbooks, and roles left over through consecutive refactors. Even in a “simple” infrastructure, success and safety depend on a vast set of shared assumption about how things work. As individuals change the systems’ behavior, the change has to be explicit, easy to understand, and easy to remember. Pieces being left around from “the old way” make it easy to make a no-longer-valid assumption.

Things We Should Add To Opsmatic

We’re constantly improving teams’ visibility into changes and important events in their infrastructure. That we were able to find when a particular recipe was great, but the experience also illuminated some gaps in our view of CM (e.g. role/run list changes, and some “meta” features to surface such changes). We’re hard at work, converting what we learned into real improvement in the product.

Parting Thoughts

As soon as we recovered from this outage, I thought “I’m going to have to write about this.” It is a great example of a complex system failure, “like the ones you read about.” It served as a great, rapid refresher course on complex system theory; it reminded us that we have to minimize coupling and interactions within our systems constantly and ruthlessly.

If you enjoyed this story (you sadist), you’ll probably like the following posts and books in the broader literature.

- The Field Guide to Understanding Human Error by Sidney Dekker, and pretty much anything else by Dekker on the subject of human error and human factors.

- Normal Accidents by Charles Perrow - a great introduction to complex systems, complete with great anecdotes from a number of different fields.

- Make It Easy by Camille Fournier is a great concise post on the importance of designing systems and processes with the operator in mind.

- Kitchen Soap Blog by John Allspaw is a great source for keeping abreast of developments in complex system failure, as well as ops and ops management in general.

- Amazon’s Epic 2011 Post Mortem - I mentioned this post in my Surge 2011 talk because it read so much like parts of the Three Mile Island nuclear accident’s description in Normal Accidents